Black History and Heroes

Educators, Entrepreneurs & Trailblazers: Black History and Heroes in Rockbridge County

Scholars and educators. Suffragists and civic leaders. Entrepreneurs and everyday heroes. For several hundred years, African American communities, institutions, and distinctive individuals have played an important role in shaping the histories of Lexington, Buena Vista, and Rockbridge County.

Many of these local trailblazers are introduced below, and historic sites associated with their stories are easily reached on two self-guided tours. The Black History Walking Tour explores downtown Lexington while the Black History Driving Tour crisscrosses the county. Both tours include a virtual map and links to supplemental articles.

LEXINGTON AND THE GREEN BOOK

A historical marker titled "Lexington and the Green Book" is located at the Lexington Visitor Center, 106 E. Washington Street, highlighting local sites that provided safe lodging and dining for African American travelers during segregation, before the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964. Mentioned on the marker are Franklin Tourist Home (operated by Zack and Arleana Franklin on Tucker St.), the Rose Inn and Washington Cafe (both on North Main Street), and the J.M. Wood Tourist Home (Massie Street). Although none of these continue to operate today, they represent the wider range of small business enterprise created by citizens in the town's local Black neighborhoods of Green Hill and Diamond Hill, offering the range of services and hospitality fronted by "The Negro Motorists' Green Book" between its first publication in 1939 and the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

HISTORIC FIGURES

Lexington: Educators, Civic Leaders & Entrepreneurs

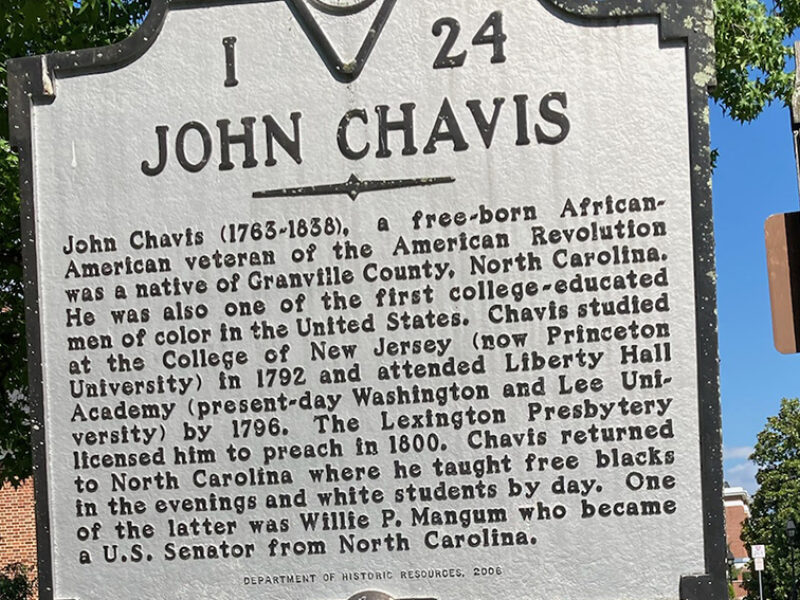

Chavis Hall, an academic building on the Colonnade at Washington & Lee University, is named for scholar and teacher John Chavis. Born a free Black man in North Carolina, Chavis studied at Washington Academy, now Washington & Lee, in the 1790s. He was one of the first college-educated men of color in the United States. The historic marker that tells his story is located on Washington Street, right across from the W&L President's House.

One of Lexington’s most successful African American businessmen, Harry Lee Walker opened a butcher shop in 1911 on North Main Street. He supplied meat to W&L, VMI, and various fraternities. Anchoring the once-vital Black business corridor on N. Main Street, the building was renamed for him, and eventually became home to Macado’s restaurant.

In 1917, Walker purchase one of the city's most notable homes, "Blandome," the large white house overlooking Lexington, visible atop Henry Street. His wife, Eliza Bannister Walker, trained as a nurse at Washington D.C.'s Freedmen's Hospital, and became a noted civic activist and poet. She hosted the statewide conference of the Virginia Federation of Colored Women at Blandome in 1921, the first year after the 19th Amendment granted women the right to vote. The Walker Entrepreneurship Program is named for the Walkers, a start-up incubator for small businesses today.

Born enslaved in 1862, Lylburn Downing attended Lincoln University and became a respected Presbyterian minister in Roanoke. A longtime civic leader, he was a passionate advocate for education for African Americans, serving on integrated statewide educational committees. His parents attended Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s Sunday School lessons at Lexington Presbyterian Church on Main Street. The county-wide African American school named for Reverend Downey was built in 1927. It sits atop Diamond Street, next to Richardson Park, which was named for local mid-20th century civic leader and Scoutmaster Leroy Richardson.

Coralie Franklin Cook, born in Lexington in 1861, was an African American suffragist, civic leader, and powerful orator. The first descendant of enslaved families at Monticello to earn a college degree, she graduated from Storer College in Harper's Ferry, and later chaired the Rhetoric and English Department at Howard University. A close friend and collaborator with Susan B. Anthony, Cook passionately advocated for women’s right to vote, especially women of color, and she helped found the National Association of Colored Women.

Rockbridge County: Trailblazers and Heroes

Edward “Black Ned” Tarr was the first free Black man to own land west of the Blue Ridge Mountains. A well-known blacksmith on the Great Wagon Road in the 1750s, Tarr also helped establish Timber Ridge Presbyterian Church. His former property and the church are located in Timber Ridge, near the junction of I-81 and Route 11 at exit 195 near Maple Hall. Downtown, a marker noting his achievements can be found at the corner of Main and Nelson Street, at the trailhead of the Rockbridge Historical Society's sidewalk "Story Stones" project heralding "The Righteous and Rascals of Rockbridge."

The model for the freed slave in the Emancipation Monument in Washington, DC's Lincoln Park, Archer Alexander was born in Rockbridge County in about 1806. His enslavers lived near the South River, not far from Timber Ridge. They later moved west – with Alexander and his wife Louisa, ancestors of Muhammad Ali – to Missouri. During the Civil War, Alexander notified Union troops of acts of sabotage by Confederate sympathizers. He later escaped to freedom.

Legally freed from slavery, Patrick Henry was hired as caretaker of Natural Bridge, a 215 foot-high limestone arch noted for its beauty, and centuries-long resort for international tourists. Henry was grated a cabin near the arch, and pursuant to an agreement with its owner – former president Thomas Jefferson – Henry paid the annual property taxes and protected the land from trespassers. Henry lived there from 1817 until his death in 1829, when is wife took over operations for traveling visitors. Established in 2016, Natural Bridge State Park is 13 miles south of Lexington.

A granite obelisk and Virginia historic marker in Glasgow, six miles south of Natural Bridge, honor Frank Padget, a skilled boatman and slave who died while rescuing passengers from a capsized bateau boat on the James River in 1854.

Check out a bateau at Jordan’s Point, a city park beside the Maury River near downtown Lexington. Historic locks and canals are visible along the seven-mile Chessie Trail, a hiking and biking trail connecting Lexington and Buena Vista.

CHURCHES AND CEMETERIES

For more than 150 years, two churches have played an important role in the African American community in Lexington. Both are a short walk from the visitor center. Visit the RHS website for more information about the churches and the two cemeteries operated for Black residents since the early nineteenth century.

The congregation of the Lexington African Baptist Church worshiped in a frame building next to the site of the current First Baptist Church (103 N Main St) for 25 years beginning in the late 1860s. This Gothic-Revival-style building was completed in 1896, and its congregation has long played an active role in the black community.

After the black and white members of the congregation at Randolph Street United Methodist Church (118 S Randolph St) separated in 1864, Black parishioners continued to worship at the church. It was later torn down and replaced with the current brick structure. Steel magnate and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie donated half of the costs of the church’s pipe organ in 1917. The parking lot just south of the church was the site of the Freedmen's Bureau School, which opened right after the Civil War (see below).

The first cemetery for Lexington’s slaves and free Black people was located near the intersection of East Washington and Lewis Streets near today’s city hall. The land was subsequently developed, and the remains from the cemetery were purportedly moved to Evergreen Cemetery in 1880, but there is little confirming documentation.

Funerals began at Evergreen Cemetery (Evergreen Place) in 1880 after the closure of the original cemetery. Traditionally considered the Black cemetery in Lexington, Evergreen covers about 5 ½ acres and is maintained by the City of Lexington, which also maintains Oak Grove Cemetery on Main Street, which had previously been renamed Stonewall Jackson Memorial Cemetery in 1949, when it took over the 18th century burial ground from Lexington Presbyterian Church.

SCHOOLS

The parking lot just south of Randolph Street United Methodist Church was the site of the Freedmen’s Bureau School, also known as the Lexington Colored Graded School. Established after Emancipation with the support of the Freedmen’s Bureau, it was one of Lexington’s first Black schools. It was operational from 1865 to 1927, when the Lylburn Downing School opened.

Once of the school's most prominent students was Lucy Diggs Slowe, raised by her aunt and uncle after she'd been orphaned in Berryville. She graduated as valedictorian of Howard University in 1908, a student of Coralie Franklin Cook, and hired by her alma mater in 1922 as the nation's first Dean of Women. A co-founder of both Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc. and the National Association of College Women, Slowe became the inaugural champion of the National Tennis Association in 1917, the first African American woman to win a national championship in any sport.

The once-segregated Lylburn Downing School (3003 Diamond St) opened in 1927, and it originally served grades one through nine. Only in 1944 did the school ofer high school diplomas. The original school building closed in 1965 following local desegregation plans, a decade after the Supreme Court's Brown v. Board of Education decision. The newer building became the home of integrated Lylburn Downing Middle School. A historic marker shares the story of the school and its namesake.

The Rockbridge Historical Society shares several informative articles and videos on its website about Lexington’s African American schools and about Lylburn Downing and his descendants.

Housed in a small building on 30th Street in Buena Vista, the Buena Vista Colored School served as the city's only Black school from 1892 to 1957. Students from first through seventh grade were enrolled here, and later walked or were bused to Lylburn Downing. The building is a Virginia Historic Landmark.

NATURAL BRIDGE

Black history in and around Natural Bridge isn’t limited to Patrick Henry. First Baptist Natural Bridge was established in 1865, one of the county's first Black churches, and large baptismal ceremonies were photographed in Cedar Creek below Natural Bridge by Black churchgoers in the late 1800s. Several homes near the arch hosted travelers of color during segregation, and one of them, Mountain View Cottage, earned a spot in the Green Book.

For a more complete look at Black history in Natural Bridge, check out Revisiting Virginia’s Frontier Icon: Black Lives at Natural Bridge from Patrick Henry & Thomas Jefferson to the Green Book.

SUPPLEMENTAL RESOURCES

"Unheard Voices of Black Lexington," is an interactive and well-annotated map documenting Black business owners during the Jim Crow era and their contributions to Lexington's history. Click on the microphone icon to listen to podcasts featuring voices from the Black community. A walking tour map that spotlights the Diamond Hill and Green Hill neighborhoods can be obtained from the Lexington Visitor Center.

The Rockbridge Historical Society maintains and shares a vast virtual archive of stories and links related to local African American history. Interpretive plaques and sidewalk pavers along Main Street also spotlight locals of note.

BEYOND LEXINGTON

Several prominent parks, museums, and historic homes showcasing Black history are within a 90-minute drive of Lexington.

Located in Hardy, the Booker T. Washington National Monument tells the story of the African American orator and teacher at his birthplace. Living historians now interpret the moment when Emancipation was announced on the former plantation, inspiring the 9-year-old Washington to a career creating nationwide professional and educational opportunities through the long years of Jim Crow. In Roanoke, travelers can explore The Harrison Museum of African American Culture. Nearby, Henrietta Lacks Plaza honors the once-credited woman who died of cancer, whose HELA cells were used to develop today's wide range of genetic therapies, cancer treatments, and scientific research.

The Frontier Culture Museum in Staunton interprets a re-created West African village representing traditional Igbo lifeways. The Igbo were among the enslaved people first brought to the Shenandoah Valley in the mid-18th century. At Monticello in Charlottesville, the From Freedom to Slavery Tour shares the stories of those enslaved at the home of president and author of the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson.

Last Updated February 13, 2026